Painting is Not Dead

Follow the Journey of One Couple as They Face an Unpredictable Frontier in their Efforts to Create a New Space

BY LAUREN AMALIA REDDING

“I do not want art for a few any more than education for a few, or freedom for a few.” ~William Morris

The Idea

It was right before a flight to LaGuardia Airport. I’d been visiting my family in southwest Florida, and my mother hovered as I packed my suitcase. Our conversation touched on long-term goals regarding my husband’s and my art career.

I lamented to her how, while immensely grateful for the full-time work we found, we had long coveted professorships. Neither my undergraduate programs nor his were ideologically interested in what we had to offer. Friends at major universities told us horror stories about department politics. We desired to teach art independently, but New York’s gargantuan price tags prohibited us from setting out on our own.

I lamented to her how, while immensely grateful for the full-time work we found, we had long coveted professorships. Neither my undergraduate programs nor his were ideologically interested in what we had to offer. Friends at major universities told us horror stories about department politics. We desired to teach art independently, but New York’s gargantuan price tags prohibited us from setting out on our own.

We needed to relocate, I told my mother, to a place with a booming population that supported culture. It had to be large enough to yield some students, along with some of the amenities we’d become accustomed to in New York. This seemed like a tall order.

I’ll never forget the look on my mother’s face. Her eyes widened and she spread her arms. “You have all of that here,” she told me.

The answer was so painfully obvious that I missed it entirely.

I flew back to LaGuardia. My husband and I kept working our day jobs, creating our artwork, and calling New York home. That conversation I had with my mother, however, lingered in the back of my mind.

I’ll never forget the look on my mother’s face. Her eyes widened and she spread her arms. “You have all of that here,” she told me.

The answer was so painfully obvious that I missed it entirely.

I flew back to LaGuardia. My husband and I kept working our day jobs, creating our artwork, and calling New York home. That conversation I had with my mother, however, lingered in the back of my mind.

After a few years, we finally acknowledged many things. We acknowledged that the internet shrunk the world. We acknowledged that the art community in our own city peaked long ago. We acknowledged that small cities are the new creative frontier, with their manageable rents and larger spaces, increasingly connected by marvelously expanding online platforms.

The conversation moved from the back of my mind to the front. It lounged there like a cat on a sunny windowsill, complete with drowsing eyes and a flicking tail. And it became more omnipresent, strengthened by the needs of my husband, and encouraged by the faith of our friends.

The conversation moved from the back of my mind to the front. It lounged there like a cat on a sunny windowsill, complete with drowsing eyes and a flicking tail. And it became more omnipresent, strengthened by the needs of my husband, and encouraged by the faith of our friends.

Our new creative frontier comes with white sand beaches and my grandmother’s Cuban cooking. It’s far from New York by plane, but not by email. Come hell or (hurricane) waters, we’re going to open H&R Studio in Naples this autumn.

Why We Chose To Be a Studio, Not a School

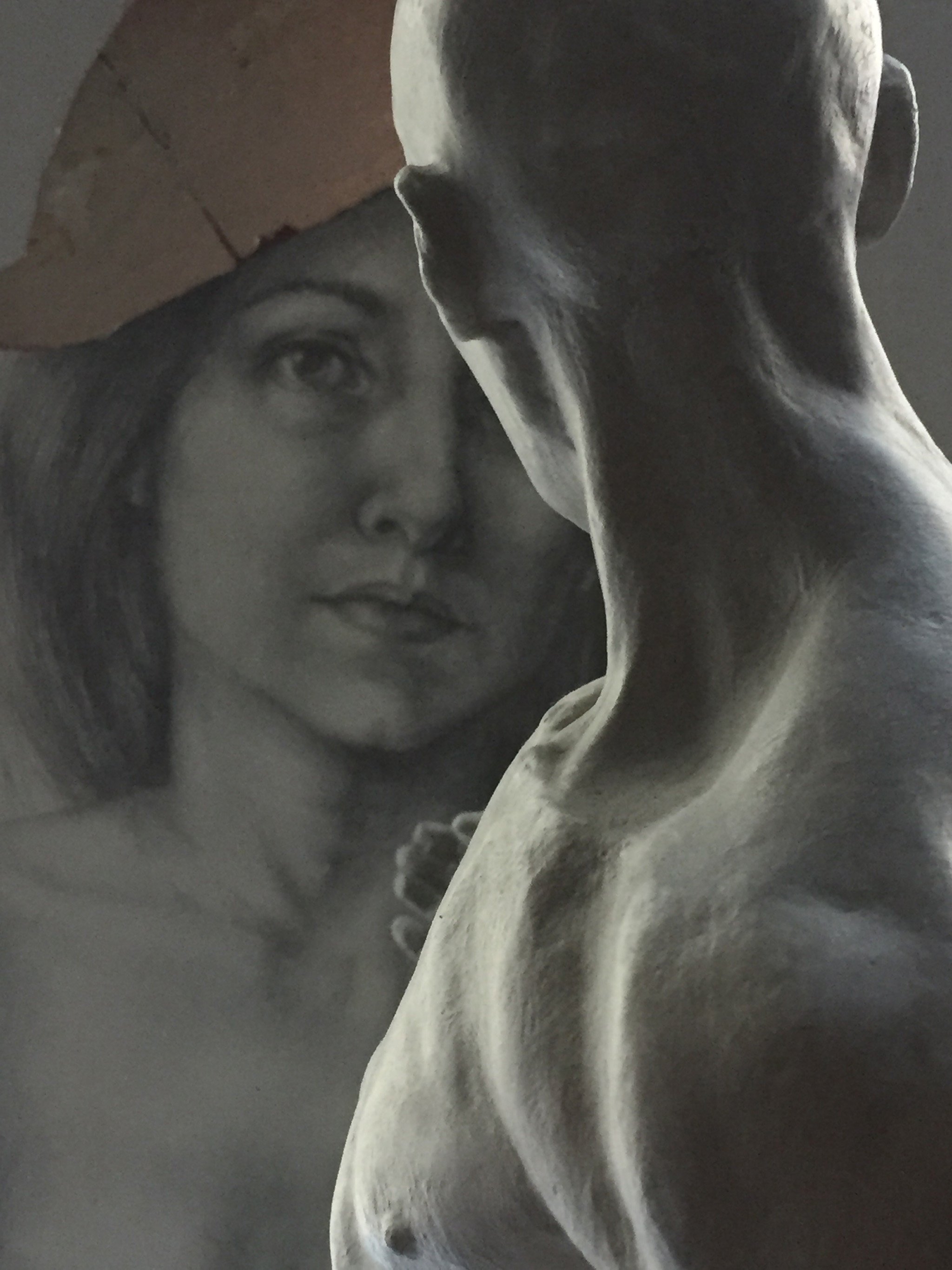

A couple of H&R Studio’s characteristics are slightly unorthodox. For one, most people opening their own business are in their forties, and we’re in our early thirties. For another, classroom space in H&R Studio will be integrated with, well, H and R’s studios. The “H” represents Harvey, my husband’s surname, and the “R” represents mine.

Practical advantages aside, this idea is hardly original. The most well-known example is the Italian Renaissance bottega, or workshop, where apprentices simultaneously worked with and learned from their masters, contributing to the overall production of artwork. Though this utilitarian setup is easily romanticized (who, after all, wouldn’t want to sketch in the shadow of Florence’s glorious Duomo?), it provided tremendous insight into the masters’ working processes.

Practical advantages aside, this idea is hardly original. The most well-known example is the Italian Renaissance bottega, or workshop, where apprentices simultaneously worked with and learned from their masters, contributing to the overall production of artwork. Though this utilitarian setup is easily romanticized (who, after all, wouldn’t want to sketch in the shadow of Florence’s glorious Duomo?), it provided tremendous insight into the masters’ working processes.

“Don’t let schooling interfere with your education.” ~Mark Twain

While we don’t expect students to imbibe our methods as faithfully as Raphael imbibed Perugino’s, we do believe that students benefit from observing as their instructors’ work originates and evolves. In turn, it holds instructors to a higher standard because we cannot just get away with talking the talk: students must see that we can walk the walk, too.

Another unusual aspect of H&R Studio is that we have no intention to seek accreditation. It’s difficult to justify the time and energy spent trying to leap through bureaucratic hoops when college enrollment has been declining steadily since 2011.[1]

Aside from dropping birth rates among 18- to 24-year-olds,[2] one wonders if the loans undertaken by so many students and their families weaken the justification for a degree.

The Class of 2017’s average student loan debt was $39,400, with the national student loan debt totaling $1.48 trillion, distributed among 44.2 million borrowers.[3]

Aside from dropping birth rates among 18- to 24-year-olds,[2] one wonders if the loans undertaken by so many students and their families weaken the justification for a degree.

The Class of 2017’s average student loan debt was $39,400, with the national student loan debt totaling $1.48 trillion, distributed among 44.2 million borrowers.[3]

A terrifying summary: the average undergraduate now leaves college nearly $40,000 in debt, and Americans owe around $620 billion more in student loans than the national credit card debt.[4]

What role does a Bachelor’s — much less its debt burden — play amidst the seismic shifts of an increasingly automated economy, and the internet disseminating information at an exponential pace?

With student bodies shrinking, we see no point in trying to enter a ring full of already-waning institutions. Besides, we can acutely relate to the debt-ridden students. We’re part of that 44.2 million ourselves.

What role does a Bachelor’s — much less its debt burden — play amidst the seismic shifts of an increasingly automated economy, and the internet disseminating information at an exponential pace?

With student bodies shrinking, we see no point in trying to enter a ring full of already-waning institutions. Besides, we can acutely relate to the debt-ridden students. We’re part of that 44.2 million ourselves.

Not a University Art Department

We’ve discussed how our setup does not resemble a school as much as a studio, but our philosophies also diverge from those of most schools. Postmodernism, and its core tenet of truth as subjective, took root in most university art departments, and now dominates them. Conceptual art is de rigueur, and skill and craft are taboo.

Students are more apt to discuss the sociohistorical implications of string dangling from a ceiling tile than they are to pick up a pencil. I and plenty of friends and colleagues have passed through postmodern and conceptual art departments that prohibited even life drawing classes. We didn’t buy it.

Students are more apt to discuss the sociohistorical implications of string dangling from a ceiling tile than they are to pick up a pencil. I and plenty of friends and colleagues have passed through postmodern and conceptual art departments that prohibited even life drawing classes. We didn’t buy it.

“The world is full of intellects whose desires have outstripped their understanding.”

~Friedrich Hayek

~Friedrich Hayek

There is value in all philosophical discussion, but the totalitarianism running rampant through most university art departments hinders students. They don’t learn the foundational skills necessary to produce representational artwork, much less learn how to deliberately break its rules. As college educations become dearer, an art class — especially one that deplores tangible skill — seems especially superfluous.

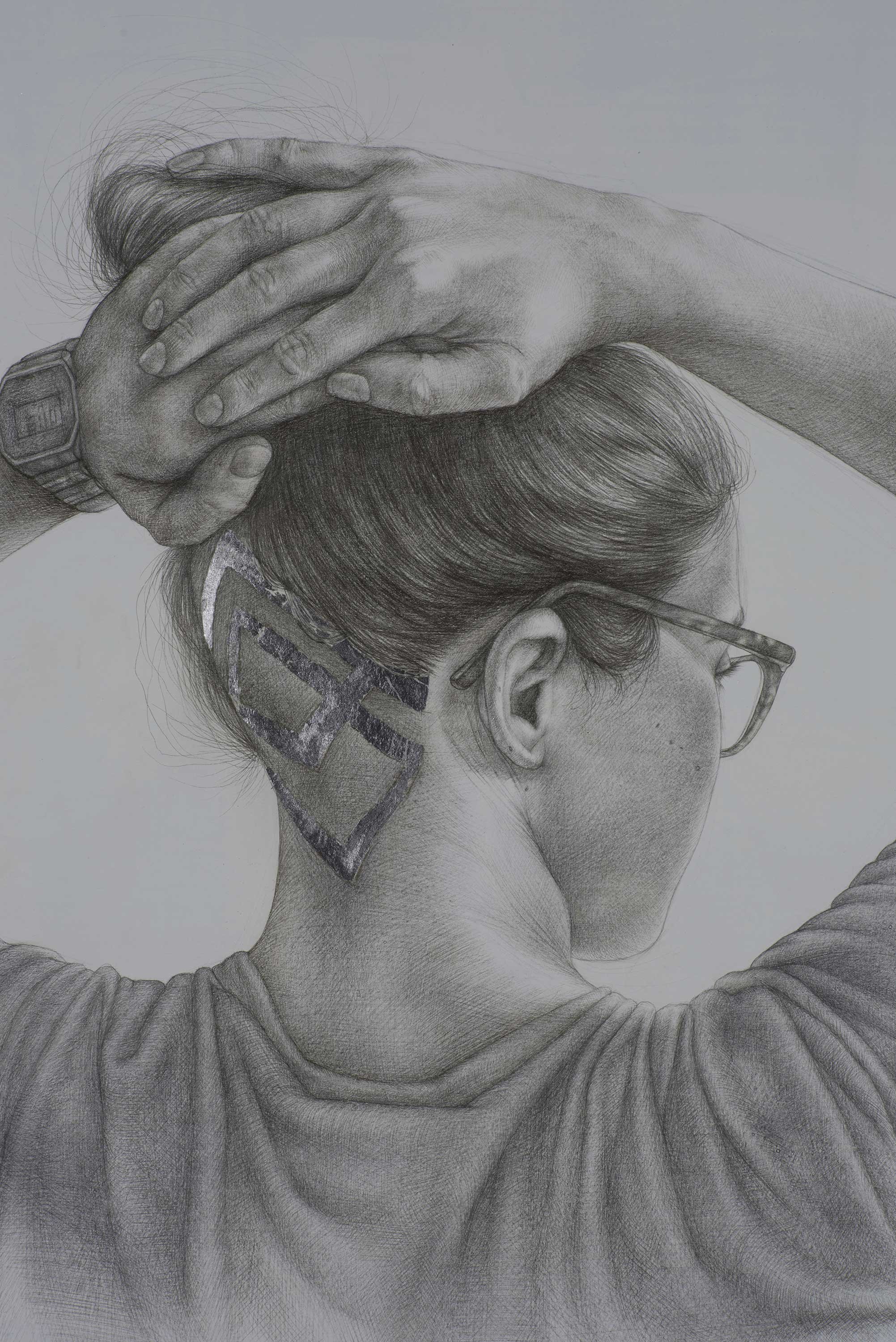

At H&R Studio, we believe that the skills required to create and appreciate representational art are universal and timeless. Anecdotally, long hours I spent working as a security officer at the Metropolitan Museum of Art provided ample time to observe visitors observing art. The Met’s growing attendance records — and increasing visitor diversity — confirm my observations.[5]

What I saw acted as a balm for my aching feet as I stood sentry: people enjoyed viewing representational art with origins often very different from their own.

What I saw acted as a balm for my aching feet as I stood sentry: people enjoyed viewing representational art with origins often very different from their own.

The commonality is the humanism inherent in the works. Anyone can peer at an object depicting a fellow human, fashioned by another fellow human, and relate. High schoolers from the Bronx marveled at Rodin. Elderly Japanese visitors admired Vermeer. The mystique of ancient Egypt attracted everyone. And visitors from nearby hospitals meandered through the galleries after receiving devastating news because, as one told me, he now needed to experience beauty more than ever.

This interest does not wane simply because professors in the ivory towers of academia tell us that painting is dead. This interest is embedded in neuroscience. It can awaken and aid us. This is the triumph of our innate understanding over their desires.

This interest does not wane simply because professors in the ivory towers of academia tell us that painting is dead. This interest is embedded in neuroscience. It can awaken and aid us. This is the triumph of our innate understanding over their desires.

Not an Atelier

As the pendulum moves away from postmodern university art departments, one might expect it to swing clear into its polar opposite: the atelier. To be frank, we’re not completely interested in that model, either. Many technical components of Bargue drawing help tremendously in visual problem solving, and we’re the first to applaud copying casts of great sculpture. After all, we’re determined advocates for representational skill. But we don’t fixate on the French Academy, and it’s not simply because of Brett’s personal preference for all things Greek, or mine for all things Florentine.

“Whatever an education is, it should make you a unique individual, not a conformist.”

~John Taylor Gatto

~John Taylor Gatto

It’s because we also advocate for the student as an individual. While ateliers impart important concepts, our goal does not wrap itself around the French Academic tradition, which, despite producing undeniably competent work, yields uniformity of execution. A class where every student’s piece looks the same would be anathema to our desires.

During my time at the New York Academy of Art, I was taught by someone who can only be described as a contemporary Neoclassicist. Though his idealization of form would have piqued even Poussin’s interest, he wanted nothing to do with turning students into a fleet of Neo-Neoclassicists.

I’ll never forget an exchange I overheard between him and another student during a life painting class. This student was an ardent Cubist. He painted even the softest of limbs into harsh, angular, architectonic shapes.

This instructor neither chastised him nor tried to change the way he painted. Rather, he spoke to the student about his love of Cubism and angles. Then he set to work, trying to help the student translate the model into the most Cubist image possible. This stimulated and energized them both.

I’ll never forget an exchange I overheard between him and another student during a life painting class. This student was an ardent Cubist. He painted even the softest of limbs into harsh, angular, architectonic shapes.

This instructor neither chastised him nor tried to change the way he painted. Rather, he spoke to the student about his love of Cubism and angles. Then he set to work, trying to help the student translate the model into the most Cubist image possible. This stimulated and energized them both.

As this instructor did not regard his students merely as acolytes, he could mute his own aesthetic voice so that their voices, instead, could ring out.

It takes humility to discard the visual language one spends years honing in deference to another’s preferred syntax. This instructor is a humble man whereas we may be too naïve to know better. But at H&R Studio, we wish to emulate that instructor by recognizing the student as an individual artist in his or her own right.

That is the crucial second half of our philosophy: we aren’t looking to franchise either postmodern or French Academic teaching. We’re looking to give students the best tools to amplify their own voices.

It takes humility to discard the visual language one spends years honing in deference to another’s preferred syntax. This instructor is a humble man whereas we may be too naïve to know better. But at H&R Studio, we wish to emulate that instructor by recognizing the student as an individual artist in his or her own right.

That is the crucial second half of our philosophy: we aren’t looking to franchise either postmodern or French Academic teaching. We’re looking to give students the best tools to amplify their own voices.

The Identity

This article outlines what we aim not to be. Whether we’re spearheading a new, market-driven trend in education, providing structure and self-expression for students, or facing the next unpredictable frontier in our own lives, we hope to be a hybrid and maverick. Only the future can designate an adequate label (if any may prove applicable). And while this article speaks about an endeavor ignited by aspirations, statistics, and philosophies, there is one person amidst all these words — or perhaps an unintentional spokesman for a select group — who, ultimately, propels H&R Studio’s purpose.

He dawdled in front of a Filippino Lippi painting near where I held my guard station. His eyes tremulously caressed the Madonna’s ultramarine blue robe, and he told me the devastating news he’d received about his wife’s health. The doctors at Lenox Hill Hospital said it was cancer. She was undergoing her first chemotherapy treatment and he couldn’t do anything other than wait. He fled to the Met, tottered past the Tiepolo and came to see Botticelli, Giotto, Fra Angelico, and his favorite, Filippino Lippi.

He dawdled in front of a Filippino Lippi painting near where I held my guard station. His eyes tremulously caressed the Madonna’s ultramarine blue robe, and he told me the devastating news he’d received about his wife’s health. The doctors at Lenox Hill Hospital said it was cancer. She was undergoing her first chemotherapy treatment and he couldn’t do anything other than wait. He fled to the Met, tottered past the Tiepolo and came to see Botticelli, Giotto, Fra Angelico, and his favorite, Filippino Lippi.

“Artworks are the most complex and diverse of human achievements, creations of free human will and conscious execution.”

~ Denis Dutton

~ Denis Dutton

A very ugly disease was ravaging someone whose life he loved more than his own. To counter that ugliness, he consoled himself with the beauty he so admired in Italian quattrocento paintings.

A Jewish New Yorker found refuge in Catholic imagery painted in Tuscany centuries ago. How complex and diverse his comfort.

We only hope that we can provide an escape as viewing art once offered a man relief. Whether the ailment is sickness or boredom, we hope to enrich. Whether the impetus is curiosity or a true calling, we hope to challenge. We hope to be a guide through a conscious execution to celebrate the free human will.

A Jewish New Yorker found refuge in Catholic imagery painted in Tuscany centuries ago. How complex and diverse his comfort.

We only hope that we can provide an escape as viewing art once offered a man relief. Whether the ailment is sickness or boredom, we hope to enrich. Whether the impetus is curiosity or a true calling, we hope to challenge. We hope to be a guide through a conscious execution to celebrate the free human will.

Setting Up a Studio: Advice & Accounting

Though H&R Studio won’t be open for a few months, the demands of opening and running a small business means that we’ve been setting it up since Winter 2018. The largest takeaways we’ve had so far center on two concepts: advice and accounting. When we began to envision H&R Studio, I immediately contacted trusted friends and family for advice. This group included successful artists and self-employed entrepreneurs in non-creative fields. Their combined diversity of experience led to a panoply of generous information, encompassing everything from web design to work schedules. They also, in turn, suggested other people with whom we should consult. We’ve implemented their advice and it’s already smoothed a couple bumps along our way.

That leads to the second concept: accounting. As a result of that advice, we connected with a great accountant. As neither of us have begun an endeavor of this scope and risk, a trusted accountant is an invaluable asset. As an ardent number-hater, it was a tremendous relief to me to find a professional with the patience to answer questions and walk us through many processes. If we tried to manage our own taxes and bookkeeping, a simple error could lead to expensive repercussions. As such, an accountant also provides us with a safeguard when dealing with the IRS by diminishing our own liability. Again, I can’t stress my dislike of numbers enough. Knowing that we have someone to help means a healthier financial future and my own peace of mind.

That leads to the second concept: accounting. As a result of that advice, we connected with a great accountant. As neither of us have begun an endeavor of this scope and risk, a trusted accountant is an invaluable asset. As an ardent number-hater, it was a tremendous relief to me to find a professional with the patience to answer questions and walk us through many processes. If we tried to manage our own taxes and bookkeeping, a simple error could lead to expensive repercussions. As such, an accountant also provides us with a safeguard when dealing with the IRS by diminishing our own liability. Again, I can’t stress my dislike of numbers enough. Knowing that we have someone to help means a healthier financial future and my own peace of mind.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Lauren Amalia Redding (b. 1987, Naples, Florida) is an artist and writer living and working in Queens, New York with her husband, sculptor Brett F. Harvey. She received her B.A. from Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois and her M.F.A. from the New York Academy of Art.

Her exhibition history began with a solo show at Chicago’s renowned Palette and Chisel Academy of Fine Arts in 2008. Since then, she has exhibited extensively, both in New York City and nationally. Her work is featured in the Mosaic House Hotel in Prague, Czech Republic, and is in the permanent collection of the Siena Art Institute Library in Siena, Italy, as well as private collections in the United States and Australia.

Lauren has also been included in Fine Art Connoisseur, Fine Art Today, and American Art Collector magazines. She was an artist in residence at the Florence School of Fine Arts in Florence, Italy, housed in Giorgio Vasari’s former studio, and she has published poetry and articles for the Pen + Brush, PoetsArtists, Art Aesthetics, PaintGuide, and the Blue Review. She curated the pivotal “Argentum: Contemporary Silverpoint” in Manhattan, and had a solo show at Menduiña Schneider Art Gallery in Los Angeles in October 2017.

In Autumn 2018, Lauren will be co-founding H&R Studio alongside her husband in Naples, Florida, with classes set to begin in January 2019.

Her exhibition history began with a solo show at Chicago’s renowned Palette and Chisel Academy of Fine Arts in 2008. Since then, she has exhibited extensively, both in New York City and nationally. Her work is featured in the Mosaic House Hotel in Prague, Czech Republic, and is in the permanent collection of the Siena Art Institute Library in Siena, Italy, as well as private collections in the United States and Australia.

Lauren has also been included in Fine Art Connoisseur, Fine Art Today, and American Art Collector magazines. She was an artist in residence at the Florence School of Fine Arts in Florence, Italy, housed in Giorgio Vasari’s former studio, and she has published poetry and articles for the Pen + Brush, PoetsArtists, Art Aesthetics, PaintGuide, and the Blue Review. She curated the pivotal “Argentum: Contemporary Silverpoint” in Manhattan, and had a solo show at Menduiña Schneider Art Gallery in Los Angeles in October 2017.

In Autumn 2018, Lauren will be co-founding H&R Studio alongside her husband in Naples, Florida, with classes set to begin in January 2019.

Artists On Art magazine ● July / August 2018 ● www.ArtistsOnArt.com