Painting from Photographs

How the Advantages Outweigh the Disadvantages

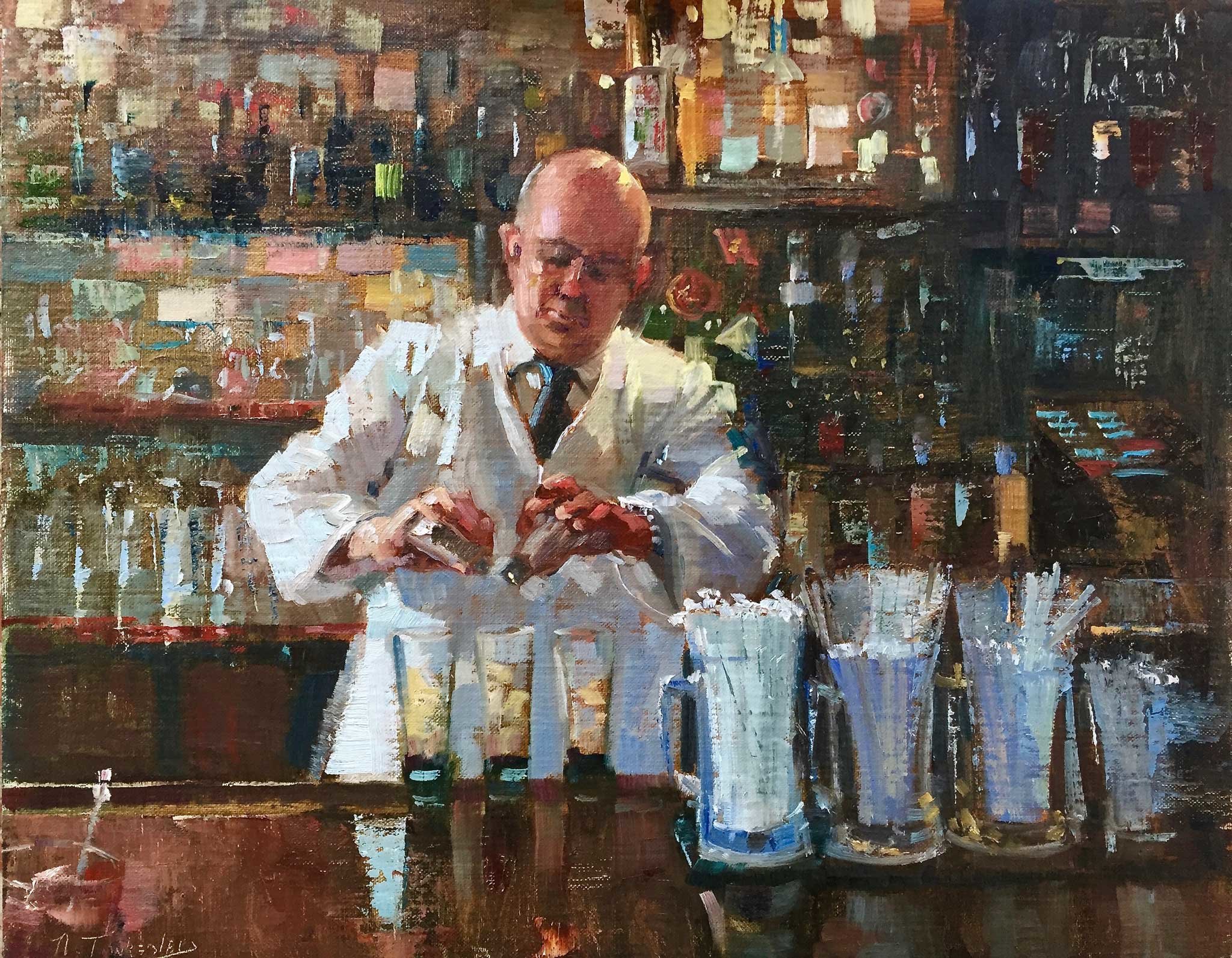

BY NANCY TANKERSLEY

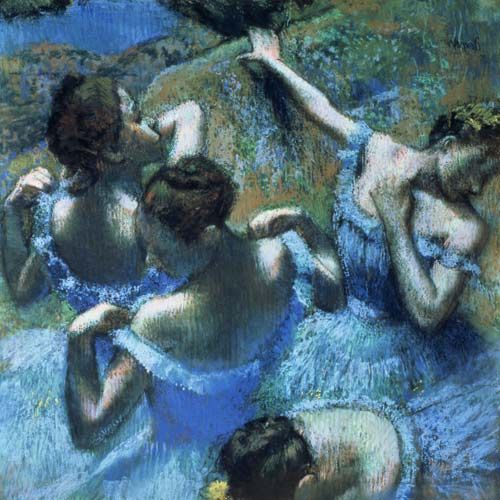

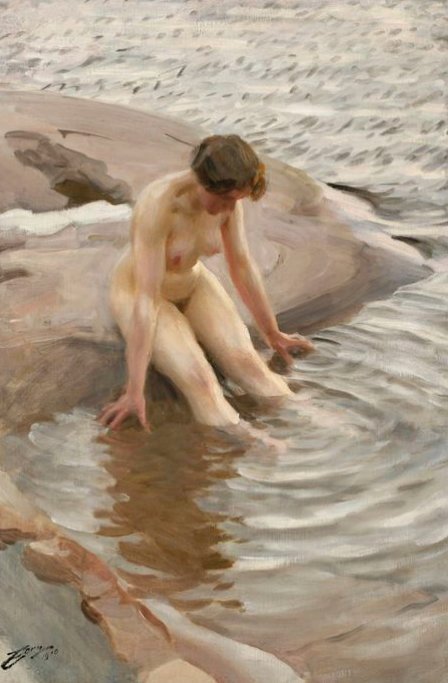

S ince the advent of photography in the early nineteenth century, artists have used the camera as a tool in picture making. The Photorealists acknowledged the modern world's mass production and proliferation of photographs, and purposefully copied photographs. But for artists schooled in the tradition of working from life, the use of photo reference was seen as "cheating." I fell in love with the painterliness of Sargent, Degas, and Zorn early on, and acknowledge that most often their work was painted from life; yet I've been painting from photographs since I first picked up a brush. Like the painters who were early users of photography, I was always a bit embarrassed about my use of the photo.

My earliest training began with lessons on drawing, shading, and perspective from Learn to Draw by artist Jon Gnagy, which I "borrowed" from my older brother. From the first lesson, I was hooked on the idea that I could possibly learn to draw as well as Gnagy. I followed his exercises and began to sketch things I saw around me, but as soon as I picked up a paintbrush to attempt to paint the head of a young Vietnamese child whose photo I saw in National Geographic, my long affair with the photograph was off and running. Occasionally I did draw portraits from life of my friends and relatives, who would sit still for 30 minutes, but National Geographic provided interesting photos of people I had never met and places I had never been.

Years later, when I began my professional career as an artist while living in Jacksonville, Florida, I painted hundreds of portrait commissions of children and adults, all of them from photographs I took. Shooting thousands of photos while following children around in 90- to 100-degree heat and humidity, I often felt more like a photographer than a painter.

But I was seeking that one expression that was most authentic for each child, and with the help of the parents we were usually able to find the right one. Often, when working from life, the subject falls into a pose that is more somber than they usually look, but the photo can capture that fleeting expression that is so characteristic of the individual.

But I was seeking that one expression that was most authentic for each child, and with the help of the parents we were usually able to find the right one. Often, when working from life, the subject falls into a pose that is more somber than they usually look, but the photo can capture that fleeting expression that is so characteristic of the individual.

At the same time, I was taking portrait lessons in the evening from Cleve Miller (a contemporary and friend of David Leffel), where we only worked from life. I also painted still life in my studio when I had the chance. But as a mother with young children at home, and a thriving portrait business, the obvious advantages to working from photos in the convenience of my home studio couldn’t be ignored.

In those years, which were filled with raising my family and frequent moves as a Navy wife, the photo was still my primary reference source. By then I was showing my figurative work and even the occasional landscape in galleries. In 2000, however, when I first joined the Washington Society of Landscape Painters and began painting en plein air on a regular basis, I began to fully realize what I had been missing.

In those years, which were filled with raising my family and frequent moves as a Navy wife, the photo was still my primary reference source. By then I was showing my figurative work and even the occasional landscape in galleries. In 2000, however, when I first joined the Washington Society of Landscape Painters and began painting en plein air on a regular basis, I began to fully realize what I had been missing.

I found the experience of connecting with what is directly in front of you, with no filters or mechanical gadgets altering your perceptions, to be a valuable and essential one. Drawing and painting from life improves your ability to see subtle difference in tone and temperature. After all, when working from life you are viewing objects in all of their dimensions; with a photo you are working with two dimensions only.

Life observation also builds your visual memory and understanding of how light affects form. With enough experience in working from life, an understanding of basic shapes and light source, and the ability to visualize in your mind, you eventually find you can invent objects and even people when needed to improve a composition.

Life observation also builds your visual memory and understanding of how light affects form. With enough experience in working from life, an understanding of basic shapes and light source, and the ability to visualize in your mind, you eventually find you can invent objects and even people when needed to improve a composition.

Historical Proof

Finding out that painters have used photography as an aid ever since the camera was invented was a revelation and affirmation that I hadn't delayed my painterly development irreversibly! Since 2000, museum curators and researchers have acknowledged the place photography has had in many of the great paintings of the last 150 years. It has been well documented that masters who sometimes used photo reference include Degas, Zorn, Picasso, Gaugin, Sorolla, Lautrec, Cezanne, and even Van Gogh.

Edgar Degas was an early fan of the camera and even stopped painting for a while to experiment with photography. Note how he printed a photograph of the same ballerina in two ways, as she was captured by camera and also in reverse (below). So he had two wonderful gestures that he could use in his compositions.

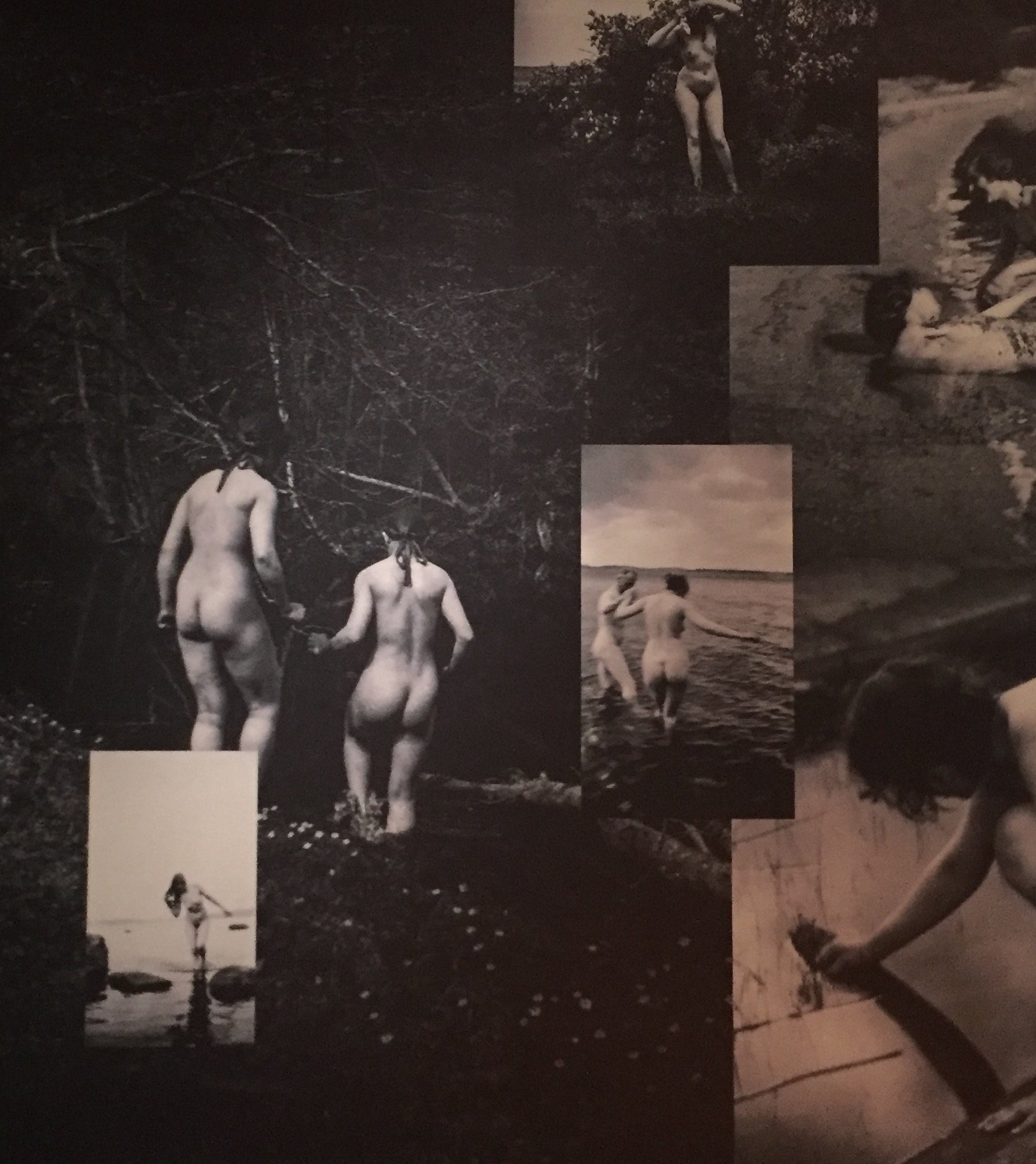

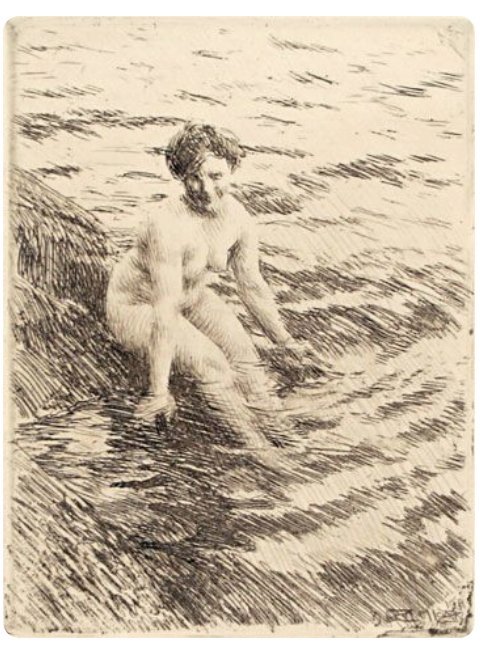

Anders Zorn was another master who used the photograph in multiple ways. He was known for taking photos of his models in black and white, and making etchings from the photos, probably to better understand the values of a scene, and later developing the etchings into oil paintings. In fact, the show of his works at the Petit Palais in Paris in 2017 ended with a wall plastered with his black and white photos of his models.

Disadvantages of Working with Photos

To me, the biggest disadvantage is that the camera sees all things equally, unlike the human eye, which sees selectively. When you look at a snapshot you will see that almost everything in the field of view is in equal focus. A trained photographer can manipulate the camera to see as the eye sees, where the focal point is in sharp focus and the unimportant elements are in soft focus or out of focus.

I tend to use the photos that are shot quickly with little thought to composition or focal point. It's later in my studio that I can look at the photos and a painting will come to my mind.

Values and colors can be affected by camera settings and the camera's inability to capture all the colors there are in nature. This was a real problem before digital photography, since the lights were often too light and the shadows were too dark.

I tend to use the photos that are shot quickly with little thought to composition or focal point. It's later in my studio that I can look at the photos and a painting will come to my mind.

Values and colors can be affected by camera settings and the camera's inability to capture all the colors there are in nature. This was a real problem before digital photography, since the lights were often too light and the shadows were too dark.

Being able to manipulate values, colors, and contrast on our computers has made this issue less of a problem.

Working exclusively from photos can sometime kill your creativity. I've seen many painters copy a photo without thought to how they might change the arrangement of objects to make a more interesting composition, or faithfully render something that lends no value to the image, simply because it was in the photo.

Distortion of form can occur depending on how the camera is held, and the artist needs to be able to recognize when that occurs.

Only working enough from life will give you the skill to know when that happens.

Working exclusively from photos can sometime kill your creativity. I've seen many painters copy a photo without thought to how they might change the arrangement of objects to make a more interesting composition, or faithfully render something that lends no value to the image, simply because it was in the photo.

Distortion of form can occur depending on how the camera is held, and the artist needs to be able to recognize when that occurs.

Only working enough from life will give you the skill to know when that happens.

Advantages of Working with Photo References

Photos allow you to capture images that would be impossible to capture from life such as quickly moving objects (dancers and athletes), and views where it would be difficult to set up an easel (such as a busy restaurant kitchen). With the advent of digital photography it is now possible to take a photo of a busy scene, such as a crowded marketplace, and on your computer then enlarge and isolate part of the image that would make an interesting painting. My paintings are often only small parts of the original photo.

My first successful painting from a photo (other than portraits) was taken from a small part of a photo I took with my first digital camera of a busy New York restaurant. When I put the photo on my computer and zoomed in on different parts of the image I discovered a scenario that I might otherwise have missed. I called it Private Conversation, and it was included in the 2004 book 100 Ways to Paint People and Figures, Volume 1 (International Artist)

.

Photos can stimulate your imagination and memory. In your studio, you can experiment with design, and combine photos to make a more interesting painting. You can select a focal point and make design decisions based upon your selection. You can flip photos (as Degas did above) and make the sizes of the objects (figure, animal, tree, house, car, tractor, etc.) as large or as small as you need it for your composition.

Be willing to deviate from all that the photo is showing you, and learn to take from the photo important and useful information such as shape, value, gesture, and size relationships. (For example, how tall was that tree compared to the house? Or, how tall was that man compared to the woman?) And even then, use your artistic license! Do you want that house to be more important? Make it bigger than the surrounding masses. Is that woman not graceful enough? Push her hip out a bit to one side. Do you want to make that pink house pop? Gray the colors of the bushes surrounding it a bit.

All of these are artistic decisions you can make despite painting from photographs.

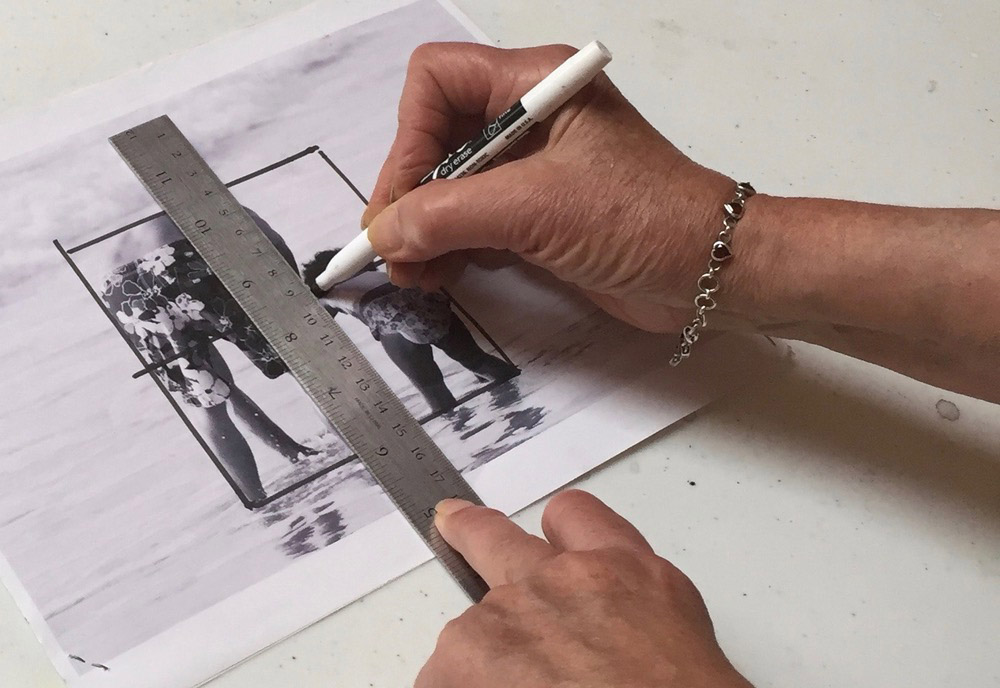

Photos are an aid to drawing and painting because they can help take accurate measurements of an object or figure (Be careful of photo distortion). Have you ever drawn the figure freeform and then discovered later that the legs had grown to an unbelievable proportion? It might have been a happy accident and you like it that way, but most likely it means you have to start over!

When I cite the advantage to measuring when working from photos I'm not talking about the graphing method that was popular with the Photorealists. In that case the photo was divided into a grid composed on equally spaced squares, and each square was carefully copied onto the paper or canvas.

What I am referring to is proportional measuring, where you take an object or figure and determine where its vertical midpoint is, or where its horizontal midpoint lies, or how a part of that object or figure lines up with another part of that object, etc.

When I cite the advantage to measuring when working from photos I'm not talking about the graphing method that was popular with the Photorealists. In that case the photo was divided into a grid composed on equally spaced squares, and each square was carefully copied onto the paper or canvas.

What I am referring to is proportional measuring, where you take an object or figure and determine where its vertical midpoint is, or where its horizontal midpoint lies, or how a part of that object or figure lines up with another part of that object, etc.

A painter’s way of measuring with a thumb and brush handle can help to determine the midpoint at the start and save you from redrawing. And a ruler on a printout of a photo can do the same thing for you.

Photos Can Help You to See Values Better

I have found it is better to paint from photos that have been converted to black and white than it is to paint from full-color photos. Converting to a black and white photo can simplify the value pattern of a scene. One of the most difficult tasks for an artist, especially a beginner, is to successfully convert color into the correct value. A simplified value pattern in black, white, and gray seems to lessen the value problem for most people, and working with only three values often makes the design stronger.

It's very easy in most computer photo programs to simplify or consolidate the values by increasing or decreasing the contrast and/or the lightness of your photo. Doing so will make some of the intermediate values drop out and become either light or dark. It’s useful to experiment with your photos to see if changing these levels will make for a better composition and suggest the mood you want.

I’ve heard it said that one of the reasons that paintings from 100 years ago were so painterly is that the photos they used were so poor. Have you ever tried painting from an old black and white photo? Sometimes the shadow side of a figure fades into a dark background. Another example is when a white dress in sunlight is invisible against the sunlit sky. If you painted only the information the photo gave you, you probably came up with a painting that flowed from dark shape to dark shape and light shapes that were connected, and had interesting edges and big shapes.

In addition to having values simplified, you can paint the colors you remember, as opposed to what the photo shows you. Have you found that the photograph is never as great as our memory of a place or experience? Perhaps our emotions "colored" our perception of a special time or place. Don't we want to convey to the viewer of our paintings the same feeling we had when standing in that place? When you aren't trying to copy the color of the photograph you are free to paint that sky as blue or that sunset as pink and orange as you remember!

The photo can give you the leisure to make sure you get the shapes right, reduce the number of values you see, spark the imagination to create an invented scene, move and insert figures and other objects into a scene — all which can improve design and complexity. Painting from life frequently (especially outdoors) forces you to make editing decisions that result in stronger compositions and focal point. If you have the right mindset, this skill can also be applied when you paint from a photograph.

I recommend equal parts of your painting time be spent painting from photo references and from life, so that you understand what the photo is not showing you, and you learn to edit a scene quickly. Somewhere along the way in my journey as an artist, I began to put the practice of using a photo reference in its proper place. As my skills as a painter have increased, I have begun to rely on the photo less and have begun to see it for what it is — a useful tool, but no more important than your creativity, memory, and intention.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Nancy Tankersley began her career as a portraitist but entered the gallery scene with figurative paintings of people at work and at leisure. Currently as she searches for the unpredictable, Tankersley moves between landscape, figures, and still life. Incorporating non-traditional tools, supports and technologies for her paintings, she remains faithful to her impressionistic style.

Active in the current plein air movement, and a founder of Plein Air Easton (Maryland), she travels worldwide participating in competitions, judging, and teaching. In 2018 she was invited to be an instructor and demonstrator at the Plein Air Convention & Expo in Santa Fe, and released her first instructional video (a workshop that is almost four hours in length) with Liliedahl Videos. In 2016 and 2017 she was invited to exhibit at the American Masters Exhibition at the Salmagundi Club in New York. Recent honors include Best of Show at the Lighthouse Plein Air Festival 2017 and the Dickinson Award for Best Painting by a Signature Member of the American Impressionist Society 2016 Annual Juried Exhibit.

She is a Signature Member of the American Impressionist Society, the American Society for Marine Art, and the Mid-Atlantic Plein Air Painters, and also holds memberships in the Washington Society for Landscape Painters and the Salmagundi Club. Founder and Director of the Easton Studio, a workshops facility begun in Easton in 2010, the artist mentors and teaches workshops and also sponsors workshops by nationally known painters.

Active in the current plein air movement, and a founder of Plein Air Easton (Maryland), she travels worldwide participating in competitions, judging, and teaching. In 2018 she was invited to be an instructor and demonstrator at the Plein Air Convention & Expo in Santa Fe, and released her first instructional video (a workshop that is almost four hours in length) with Liliedahl Videos. In 2016 and 2017 she was invited to exhibit at the American Masters Exhibition at the Salmagundi Club in New York. Recent honors include Best of Show at the Lighthouse Plein Air Festival 2017 and the Dickinson Award for Best Painting by a Signature Member of the American Impressionist Society 2016 Annual Juried Exhibit.

She is a Signature Member of the American Impressionist Society, the American Society for Marine Art, and the Mid-Atlantic Plein Air Painters, and also holds memberships in the Washington Society for Landscape Painters and the Salmagundi Club. Founder and Director of the Easton Studio, a workshops facility begun in Easton in 2010, the artist mentors and teaches workshops and also sponsors workshops by nationally known painters.

Artists On Art magazine ● July / August 2018 ● www.ArtistsOnArt.com