How Pretty Pictures Transformed into a Lifeline

BY JULIE ASKEW

“Study the science of art. Study the art of science — especially learn how to see. Realize that everything connects to everything else.” ~Leonardo da Vinci

F or a long time it had been haunting me. And here I was again, painting another potentially successful wildlife painting of a cheetah — in the correct setting with all the elements I wanted, just waiting to be added to my composition.

And then it hit me. What am I doing? Painting yet another pretty picture? No way. It has to make a difference. Paintings with a purpose. They must convey a message, one that is on my mind all the time: the connection between all the species, their interdependency and role in the food chain, and how climate change and human behavior now endangers all of it. I decided there and then to change the direction of all my painting, and I haven’t looked back since.

And then it hit me. What am I doing? Painting yet another pretty picture? No way. It has to make a difference. Paintings with a purpose. They must convey a message, one that is on my mind all the time: the connection between all the species, their interdependency and role in the food chain, and how climate change and human behavior now endangers all of it. I decided there and then to change the direction of all my painting, and I haven’t looked back since.

This is how the idea of my project called LIFELINE began, before developing into a multidisciplinary concept of art, science, field expeditions, media production, and active eco-education for schools and orphanages all over the globe. My training as a scientific illustrator is now key to the extensive wildlife research and environmental studies that is developing into paintings.

The educational aspect is paramount to the Lifeline idea. Art as a tool for awareness; it creates a need to protect what you depict. And it all starts with education. To stress the urgency, I started "ASAP!" — the Lifeline Art Science Awareness Program.

The educational aspect is paramount to the Lifeline idea. Art as a tool for awareness; it creates a need to protect what you depict. And it all starts with education. To stress the urgency, I started "ASAP!" — the Lifeline Art Science Awareness Program.

My experience is that most adults, and even teenagers, are already quite set in their ways and views of the world. So I decided to use information from the Lifeline research expeditions to create ASAP! awareness packs for children. The packs include art and literature projects — promoting environment, nature, and culture preservation.

Regardless of culture, religion, and geography, it is first of all vital to respect our human differences and points of view. The unknown is often perceived to be dangerous or at least suspicious. But different cultures have different ways of solving problems. And our ecosystems need diverse and adaptable solutions, based on local knowledge.

Regardless of culture, religion, and geography, it is first of all vital to respect our human differences and points of view. The unknown is often perceived to be dangerous or at least suspicious. But different cultures have different ways of solving problems. And our ecosystems need diverse and adaptable solutions, based on local knowledge.

Only when we work together can we coordinate the efforts to preserve our planet. Laying the foundation now can create a sustainable future, which is why Lifeline appeals to respect, based on knowledge.

I am proud to say that right now (and new ones apply daily), 11 schools in Kenya and Uganda, two orphanages in Tanzania, a jungle school in Honduras and an orphanage in Nepal have signed up to receive ASAP! Lifeline education packs, creating informed artwork from recyclable or natural materials, inspired by Arab culture and Islamic art.

I am proud to say that right now (and new ones apply daily), 11 schools in Kenya and Uganda, two orphanages in Tanzania, a jungle school in Honduras and an orphanage in Nepal have signed up to receive ASAP! Lifeline education packs, creating informed artwork from recyclable or natural materials, inspired by Arab culture and Islamic art.

The Lifeline Paintings

The adult cheetah is mainly solitary and needs large areas to avoid conflicts with other predators. Human encroachment on their territory and lack of prey due to the bushmeat trade now means that the cheetah in Africa is facing the ultimate crisis. The gene pool is now too small to maintain a healthy population. Urgent attention to this situation is vital for its survival.

Lifeline 1 depicts the basic concept of predator, scavenger, and prey — the natural links and the fragility of the ecosystem. I was contemplating a way to show how the scavengers rely on the predators, and suddenly found the cheetah’s spots turning into vultures. Red, being the color of both life and death, is therefore only used in this painting where the life-lines cross the impala.

Lifeline 2 is a painting that takes the same concept a step further. The ecosystem that depends on the lion, wildebeest, and other herbivores is complicated. I needed to include more elements. Lions have been deemed vulnerable to extinction since 1996, yet numbers are still falling as hunting and encroachment is prevalent.

It is unfathomable to me that hunting is still considered legal by some. Some 100 years ago we had around 200,000 lions spread over Africa, the Middle East and Asia. In the last 20 years alone, 70,000 lions have disappeared, and the total population is now close to 20,000.

It is unfathomable to me that hunting is still considered legal by some. Some 100 years ago we had around 200,000 lions spread over Africa, the Middle East and Asia. In the last 20 years alone, 70,000 lions have disappeared, and the total population is now close to 20,000.

With fewer predators, over-grazing has a cascading effect on the ecosystem, affecting insects, birds, small mammals, and reptiles. The wildfires that are necessary for rejuvenation don't happen, and so the vegetation changes faster than the herbivores can adapt. This also affects the natural migration patterns.

Creating a design that could convey all this information in all its desperation was an artistic challenge, and I found that the painting changed as I progressed. If the story is intense enough, one needs to let a painting evolve during the painting process. In this case, that was important for both me and the painting.

Creating a design that could convey all this information in all its desperation was an artistic challenge, and I found that the painting changed as I progressed. If the story is intense enough, one needs to let a painting evolve during the painting process. In this case, that was important for both me and the painting.

The Last Elephant

On a research trip in Tanzania, it became clear how desperate the elephant crisis has become. There are no excuses and no ecological explanations. It is purely a case of humans destroying the population of elephants at an alarming rate. A mind-blowing 60 percent of Tanzania’s elephants were slaughtered in the seven years between 2007-2014 — one every 15 minutes. The African continent as a whole is losing this sensitive animal, which possesses emotions including grief and longing, and is equipped with a vast memory and long distance communication ability, which is yet to be understood by humans.

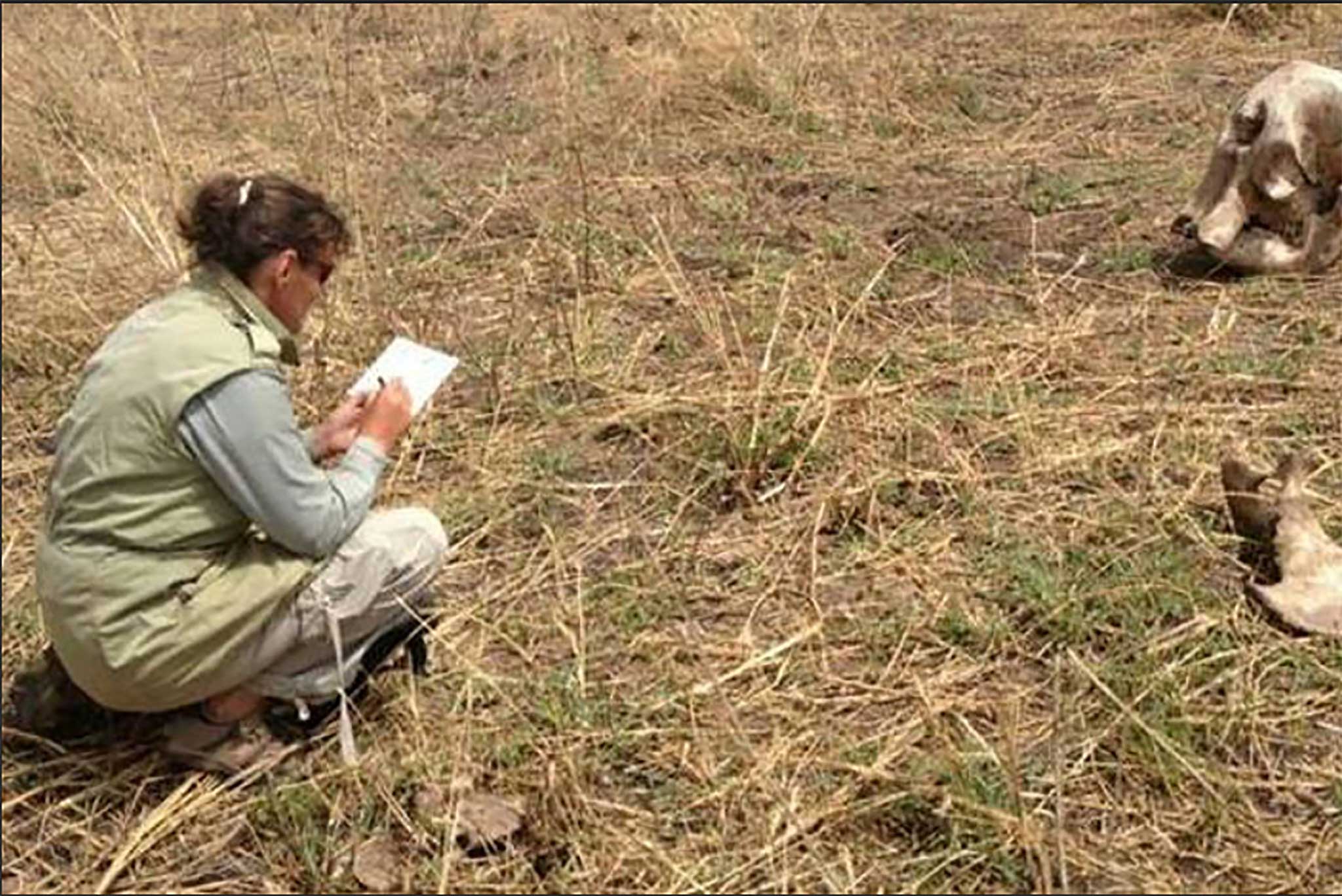

Lifeline 3 had to happen, as this desperate story is crying out to be painted. An elephant skull I came across near a swamp dominates the canvas. The small creature perched atop the skull is a rock hyrax. Despite its diminutive size, genetically it is the species closest to the elephant — and it will be all we have left by which to remember the last elephant.

Lifeline 3 had to happen, as this desperate story is crying out to be painted. An elephant skull I came across near a swamp dominates the canvas. The small creature perched atop the skull is a rock hyrax. Despite its diminutive size, genetically it is the species closest to the elephant — and it will be all we have left by which to remember the last elephant.

The Science of the Art

As mentioned earlier, in my research, sketching, and painting, I increasingly find my training as a scientific illustrator helpful. This discipline instills accuracy to a scientific level. Getting the information down on paper correctly is paramount. One dot in the wrong place, and you have changed the species of a butterfly. Or an artery slightly off center would potentially be catastrophic if your scientific illustration is followed by a vet student. One needs to know the subject intimately, doing research and working from life.

The elephant skull in Lifeline 3 is painted life size and true in form and detail. The rock hyrax is also to scale and life size, so I draw (literally) on my knowledge of the anatomic intricacies of the animal. However, the painting technique and composition would generally be considered fine art, as it is identical to the technique used for portraits. As an artist, I of course need to invent and improvise and I allow myself that freedom in the composition of my Lifeline paintings. It is blending these disciplines that allows me to create scientifically accurate works, while telling the story I have composed in a relatively loose, painterly manner and with thick paint.

Sketching

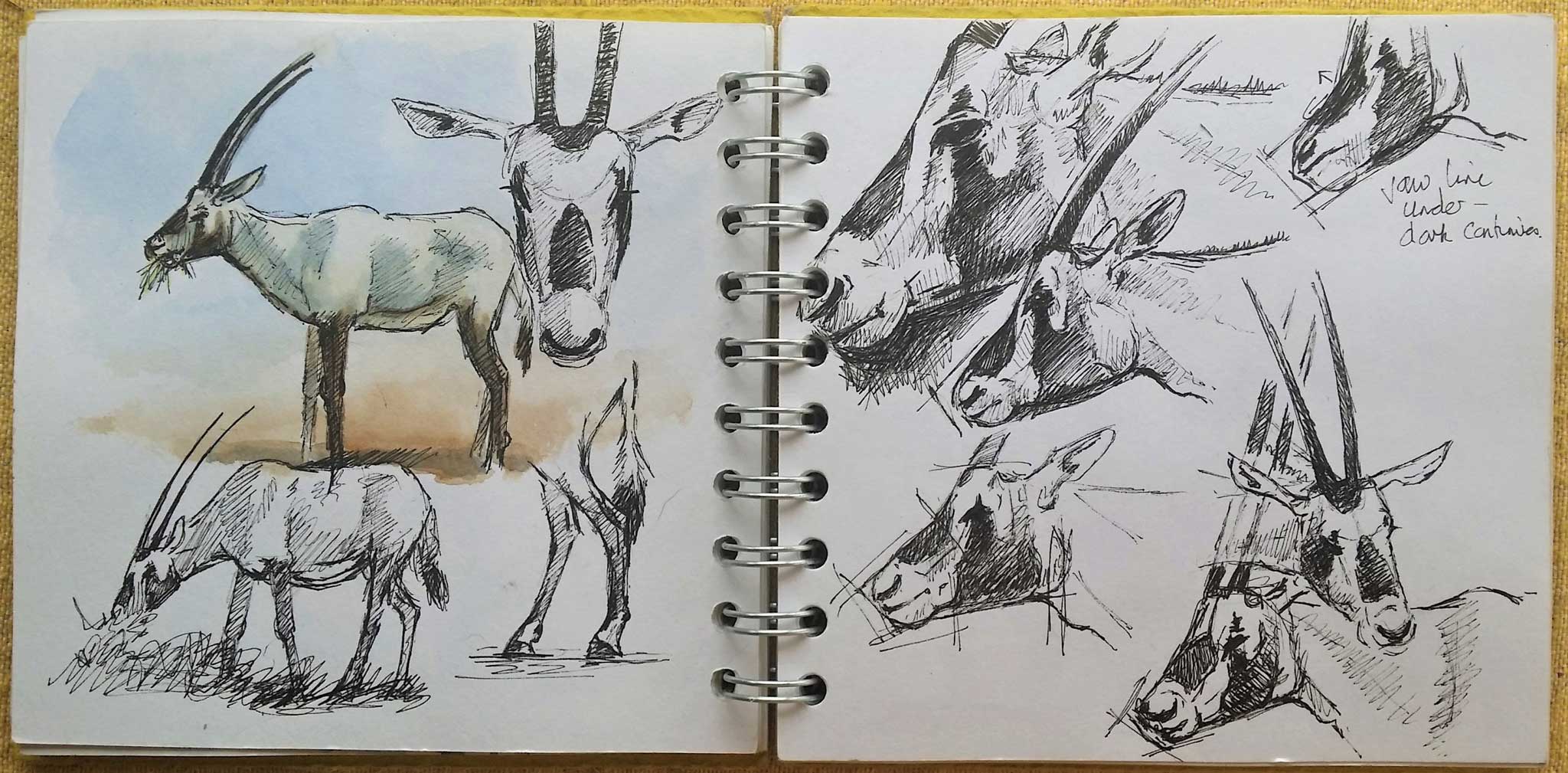

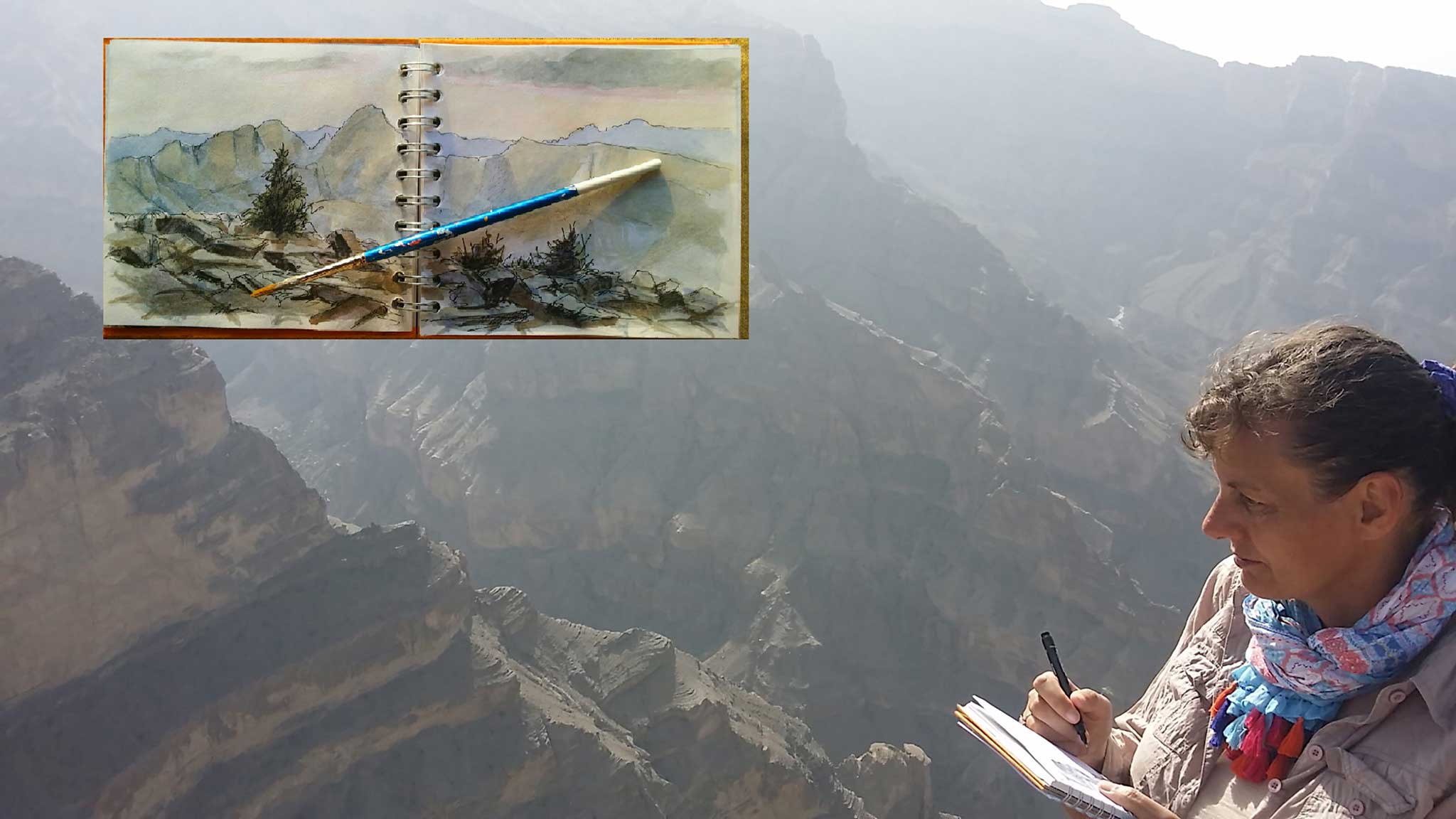

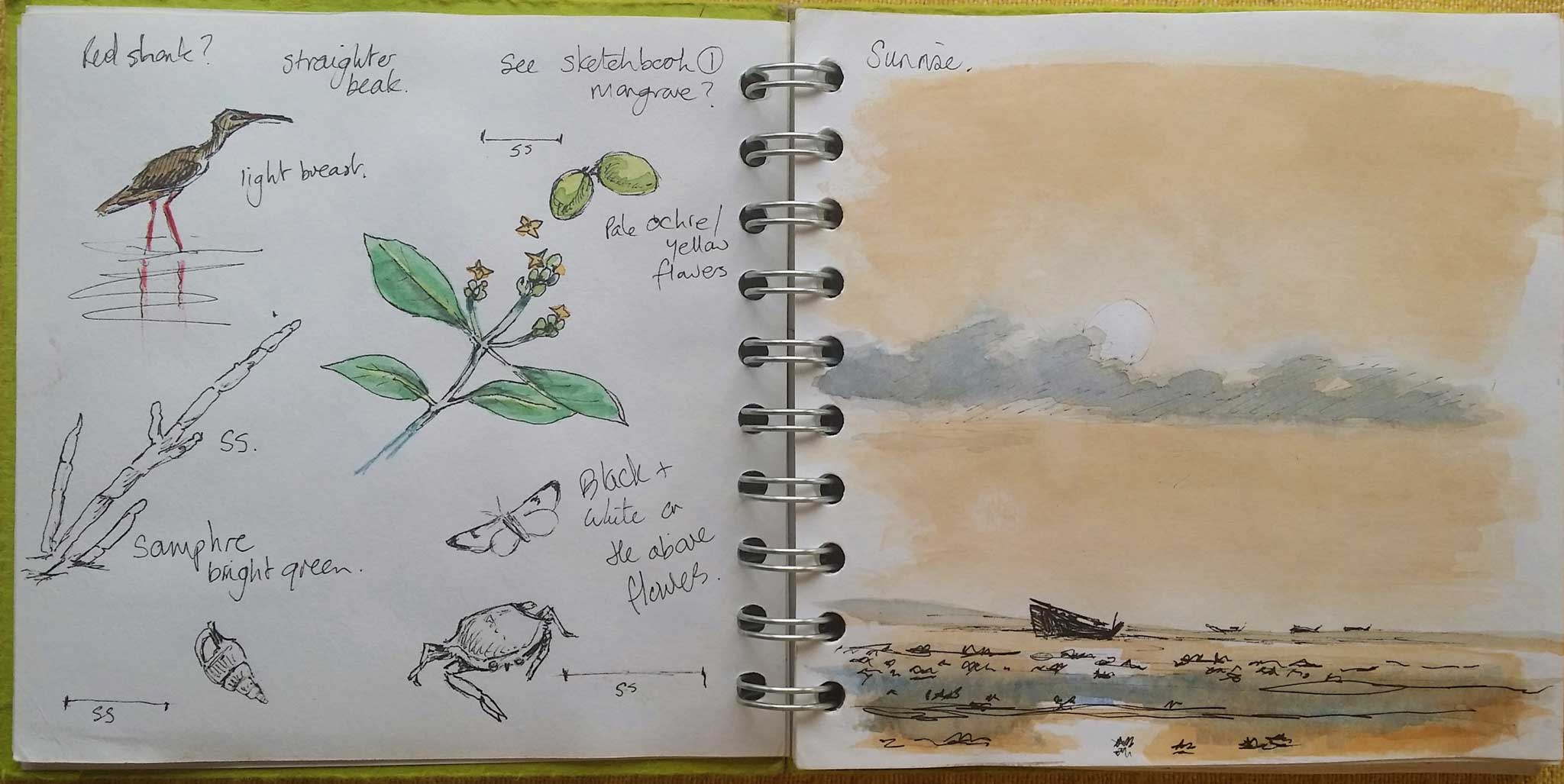

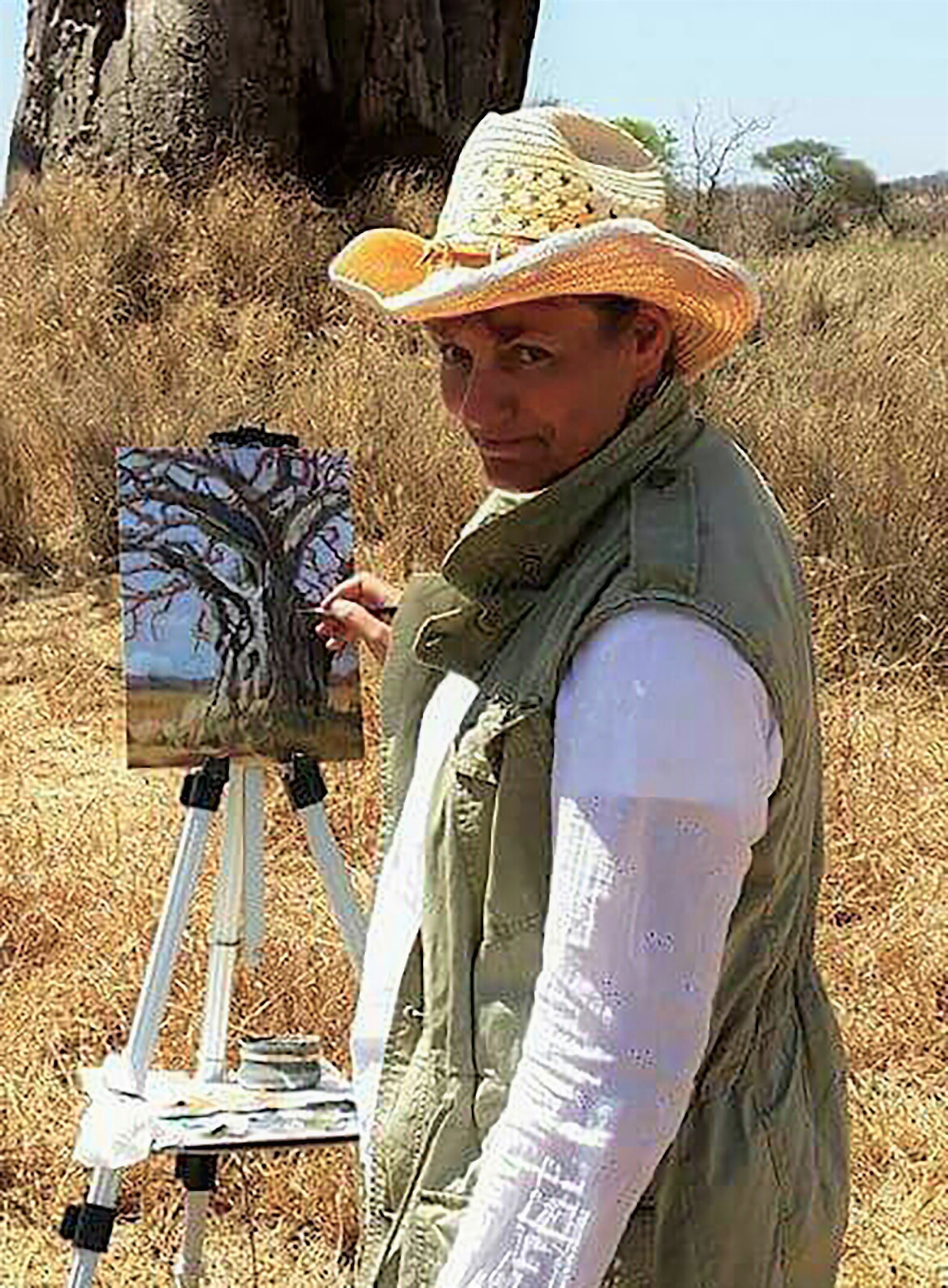

No painting without sketching: all my painting is based on field studies. I never paint what I haven’t seen with my own eyes — that means having sketched it first. Sketching is something I have done for many years and I have suitcases full of field sketchbooks. I record all my findings and observations in sketches and plein air paintings (in-the-field, within-an-hour work) and use it all for reference in the studio. I sketch in pen, which forces me to get it right the first time without correcting.

Sketching is all about observation and if you carefully observe your subject or scenario, it is quick to put it down on paper. (Yeah, I know . . . but with tons of practice it IS actually that easy.)

Sketching is all about observation and if you carefully observe your subject or scenario, it is quick to put it down on paper. (Yeah, I know . . . but with tons of practice it IS actually that easy.)

I sketch on the go, in a bumpy vehicle or while walking; my pen is ever active. I use 6-by-6-inch Pink Pig field sketchbooks; they are tough and have perfect paper. And they look cool too. I prefer this size sketchbook — it shoves down the belt of jeans if you are climbing sand dunes or out in rough terrain. And they are a handy size to hold and work in when moving. I add watercolors, either on the spot or as soon as possible, while the colors are still fresh in my mind.

The field work in sketchbooks and plein air pieces are my main inspiration and reference. Back in my studio I stand them on the easel when I design my paintings. I use some photographic reference purely for atmosphere or details, but as a tool only, since photographs are both inaccurate and flat. And quick sketching allows you to improvise, compose and interpret on the go.

The field work in sketchbooks and plein air pieces are my main inspiration and reference. Back in my studio I stand them on the easel when I design my paintings. I use some photographic reference purely for atmosphere or details, but as a tool only, since photographs are both inaccurate and flat. And quick sketching allows you to improvise, compose and interpret on the go.

When creating art about environmental issues, it is important to remember that we ourselves are part of nature. Not only do we affect it, but we cannot exist without it. I therefore find it important to include the human form in Lifeline paintings. Lifeline 4 is one such piece.

In the beginning of the twentieth century, it was thought that the red crowned crane had disappeared. The cranes live in marshlands, and as these were replaced with rice paddies, they were no longer ever seen. A tiny population was found, and thanks to intense conservation efforts, around a thousand birds can now be found in groups on Hokkaido Island, Japan, as well as in Korea and China.

The numbers are still far too low, and because of ever-expanding rice cultivation, critically endangered. The red crowned crane mates for life and is sacred in Japan, depicted throughout the centuries in art and on clothing as a cherished symbol of luck and longevity.

In the beginning of the twentieth century, it was thought that the red crowned crane had disappeared. The cranes live in marshlands, and as these were replaced with rice paddies, they were no longer ever seen. A tiny population was found, and thanks to intense conservation efforts, around a thousand birds can now be found in groups on Hokkaido Island, Japan, as well as in Korea and China.

The numbers are still far too low, and because of ever-expanding rice cultivation, critically endangered. The red crowned crane mates for life and is sacred in Japan, depicted throughout the centuries in art and on clothing as a cherished symbol of luck and longevity.

For years, I have had a beautiful Kimono adorned with red crowned cranes. While recently attending a Japanese wedding in Yokohama (in the snow), guests were wearing the elegant kimonos in a variety of rich satin and silk colors and the painting Lifeline 4 was born in my mind.

I used traditional Japanese symbolism of specific colors to highlight the plight of the red crowned crane:

Green: eternal life. The green Lifeline divides past and present.

Black: mystery

Yellow: courage and beauty

White: death

Red: danger

If we lose our focus and drop our guard for just a moment, our most cherished wildlife symbols will become only a story from the past. Can we really accept a Japan without cranes and an Africa without elephants?

I used traditional Japanese symbolism of specific colors to highlight the plight of the red crowned crane:

Green: eternal life. The green Lifeline divides past and present.

Black: mystery

Yellow: courage and beauty

White: death

Red: danger

If we lose our focus and drop our guard for just a moment, our most cherished wildlife symbols will become only a story from the past. Can we really accept a Japan without cranes and an Africa without elephants?

Lifeline 5 has become a symbol and icon for my project. Cave paintings and recent research have confirmed that humans were a main contributor to the extinction of the mammoth. And now we humans are doing it again, wiping out the elephant.

The circle of life in the painting brings us back to repeat the same mistakes. The burning of tusks only has symbolic value and is ultimately not going to save man from himself. A mind shift is required to change our attitude towards any living being.

Lifeline Research Expeditions

The Lifeline research expeditions set out to explore pressing wildlife conservation issues and how indigenous peoples fit into the story.

Just back from the Sultanate of Oman in Arabia, our main focus was the conservation story of the Arabian oryx. Extinct in the wild due to hunting, this is one of the few real success stories, and goes to show how international cooperation can mend our mistakes. Nine individual oryx were found in private collections and brought to a zoo in Arizona. Intense efforts brought this iconic animal back to its origin and it is now thriving in a large reserve the size of Luxembourg, under the intense protection of the Office for Conservation of the Environment, local Bedouin, and dedicated expert biologists.

Just back from the Sultanate of Oman in Arabia, our main focus was the conservation story of the Arabian oryx. Extinct in the wild due to hunting, this is one of the few real success stories, and goes to show how international cooperation can mend our mistakes. Nine individual oryx were found in private collections and brought to a zoo in Arizona. Intense efforts brought this iconic animal back to its origin and it is now thriving in a large reserve the size of Luxembourg, under the intense protection of the Office for Conservation of the Environment, local Bedouin, and dedicated expert biologists.

To protect the animals, the reserve — which also includes two endangered species of gazelle and the ibex — is not open to the general public, and it probably won’t be until wildlife becomes more important to people than money.

It was therefore a huge privilege to spend extensive time with these elegant, iconic animals in their natural habitat, and gather information from the expert keepers of this national treasure of Arabia. So several oryx Lifeline paintings are now on the easel.

It was therefore a huge privilege to spend extensive time with these elegant, iconic animals in their natural habitat, and gather information from the expert keepers of this national treasure of Arabia. So several oryx Lifeline paintings are now on the easel.

My principle is to have seen everything I paint in its natural environment. Field expeditions are therefore an essential part of my work. With my insistence on scientific accuracy, we now have a team of advisors, two field biologists, ,and an indigenous peoples expert on the Lifeline team. To document the expeditions I have a media producer, so the concept has grown and now includes both Lifeline Expeditions and Lifeline Media.

As the ASAP! Lifeline awareness packs are being created and sent out to schools and orphanages, it is our goal that they become an integral part of the Lifeline concept. With art as a tool, children can be empowered to better understand unfamiliar cultures, the diverse nature we inhabit, and the preservation of it. The key is education, and scientifically sound knowledge can change the future for us all.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Julie Askew has works in private and public collections including The Nature in Art Museum, UK; The Royal House of The Sultanate of Oman; Chatham Museum, British Army, UK; His Highness Sheikh Mohammed Bin Zayed Al Nahyan, Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi.

She is the founder of Oman Wild Art International Juried Exhibition and a founding member of Artist Ambassadors Against Poaching.

She is the founder of Oman Wild Art International Juried Exhibition and a founding member of Artist Ambassadors Against Poaching.

Artists On Art magazine ● July / August 2018 ● www.ArtistsOnArt.com