Learn about a device called the “graticola,” which Italian artist Antonio Mancini came to rely on for his drawings and paintings.

BY MATTHEW INNIS

His paintings were done through a wire grille, whose squares correspond with a grille before the sitter. The marks of the grille remain. The sitter being, as it were, pinned down, retained of his mobility alone the facial expression. But, trembling and snorting within that restriction, there is an extraordinary vivacity, there is power and a dashing impasto.¹ – Walter Sicket, 1927

While in his early thirties, the Italian artist, Antonio Mancini, began experimenting with a mechanical drawing aid which he would later come to rely upon extensively for executing his paintings. He called this device the graticola, and although it closely resembled the Dürer Grid the great masters had employed centuries earlier, Mancini’s own use of this tool was as peculiar as the artist himself. Despite any doubts the odd, little Italian received about the efficacy of the grid’s application, Mancini justified his use of the device, claiming, “the advantages I derive from it are unlimited.”²

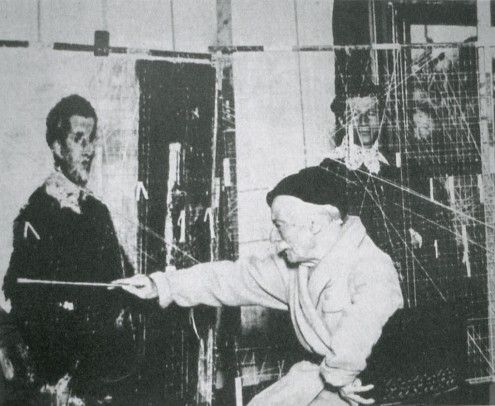

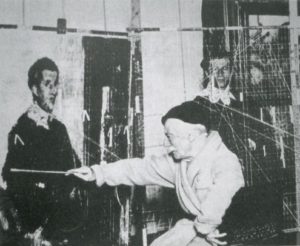

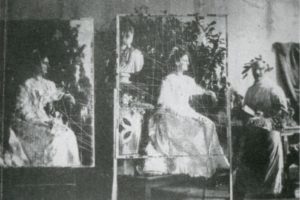

Mancini’s graticola system consisted of two identical wooden frames, each of which started with strings or wires stretched both vertically and horizontally across their middles in order to create a grillwork of squares. One of these frames was placed before the artist’s canvas, while the second frame was placed between the artist and the model, providing a screen through which to view the subject. Focusing on one sector of his view of the model at a time, Mancini would then paint a somewhat abstracted representation between the corresponding strings floating before his canvas. As the painting progressed, Mancini further segmented the screens by adding matching strings to each frame, sometimes diagonally, as dictated by the contours and angles of his sitter’s pose.

Related Article > Drawing as a Way of Seeing

In 1907, dramatist Lady Augusta Gregory sat for Mancini in Dublin. Her account of the experience is as follows:

I sat in a high chair in an old black dress, in front of a curtain lent by Miss Purser. Mancini set up a frame in front of me. He pinned many threads to this, crossing one another; their number increased from day to day, becoming a close network. The canvas on which he painted was crossed little by little with a like network. This — as he would explain in almost incomprehensible Italian — was not his own method, but had been the method of some great master. Having put up a new thread or two, he would go to the very end of the long room, look at me through my net, then begin a hurried walk which turned to a quick trot, his brush aimed at some feature, eye or eyebrow, the last steps would be a rush, then I needed courage to sit still. But the hand holding the brush always swerved at the last moment to the canvas, and there in its appropriate place, between its threads, the paint would be laid on and the retreat would begin.³

In this description, Mancini’s placement of the grid before the model, and even the addition of the bisecting diagonal lines within the frame, was very traditional, but his utilization of the second, stringed grid placed against the canvas was an oddity. Why he chose to use the strings, rather than drawing the corresponding grid directly on the canvas and painting over it as he progressed, was never disclosed. In using the strings in this manner, Mancini often created an embossed image of the grid in the oil paint: if this was an intention of his when he began experimenting with the grid, it is uncertain.

What is also unknown is why he wrapped some strings in paper, and if he exchanged the paper during the procedure. Perhaps the paper was added to increase the paint texture, or perhaps as he painted, the strings became obscured by colors, so the paper was necessary to make the lines more distinct when viewed from a distance, as was his habit.

That Mancini would step back across the room to view the model and canvas simultaneously, would indicate that he was practicing sight-size, much like his contemporary, John Singer Sargent. The two grids being of the same dimension seems to support this idea. If Mancini were not confident in his ability to visually translate the measurements from the model to the painting, then maybe the grid helped him in his stroke placement. However, if this were the case, then it seems the grid would eventually be discarded as Mancini’s ability to work sight-size improved.

In Katie Swatland‘s “Learning from Richard Schmid,” volume three, Schmid offers his thoughts on Mancini’s use of the grid. “The real reason Mancini used this graticola was to make himself, while in the act of painting, to forget that what he was painting were things, like flowers, but rather that they were shapes of color! We think we are painting flower petals, a nose, or an eye, when what we are really seeing are the shapes of color that come together to make up what we are seeing. When Mancini looked at his subject through those little squares of his device he was forcing himself to look at his subject as an abstraction. He was forcing himself to see it simply as and arrangement of shapes of color, value, and edge.”⁴ This is likely to be true, but as the same level of abstraction appears in his work predating his use of the graticola, then it is still a curiosity as to what genuine benefit Mancini gained by the device’s use.

For most, the use of a grid would indicate a desire for representational precision and a need to slow down for the sake of accuracy, yet by most accounts (see varying description by John Jacobsen, below) of Mancini’s work routine, he painted with much energy, fairly attacking his canvas Leonardo Bianchi, a doctor who treated Mancini during the artist’s stay in Naples mental hospital, said this of Mancini’s procedure:

When [Mancini] was ready to paint he placed himself in front of the canvas at a distance of four to five meters, prepared the brushes and colors, fixing the canvas every now and then with an acute and penetrating glance, almost as if he wanted to find the point on which to settle his eyes, to discover there the images that he almost saw projected on the canvas, and then he ran towards [the canvas] with the brush gripped in his hand, delivered three or four rapid blows with the brush like a fencer and then quickly drew back again, and then repeated it again towards the canvas. In this way, after seven or eight attacks, the figure was beautifully sketched out with a breath of life seeming to exhale with vigor from those shapeless colors.⁵

Mancini’s biographer, Saveriò Kambo, also indicates that the artist painted with energy, and a near aggression:

… as the excitement of creation little by little takes hold, he becomes silent and somber, and his face is transformed and contracts almost as if pain. His eyes glitter. Words tumble from his lips while, with youthful vigor he advances restlessly back and forth before the canvas, nervously delivering three or four blows of the brush and drawing back to measure the result. His excitement grows steadily as the work proceeds.⁶

Perhaps the graticola was just an experiment which became a crutch for Antonio Mancini, or perhaps it was a necessary divider which enabled the troubled artist to narrow and keep his focus during a process which obviously left him overwhelmed. In 1893, the Dutch artist, John J. Jacobsen, left probably the best account of Mancini’s method, which not only described his process, but also the mania and anguish the artist suffered while creating:

“In the last years he’s been working with his system of squares — he spans his frame with slanting lines with paper glued to them, pins pieces with paint on them to the canvas and to the frame — ‘pour voir les tons- les valeurs.’ That means everything to him. I’ve only heard him use the word ‘color’ a couple of times. Mrs. Mesdag’s words, that Mancini is a great ‘tonist,’ form a powerfully correct critique. He searches for nothing other than tone. And this he searches for with all his soul, bringing the colors halting and jerking to the canvas and whenever he approaches his canvas to … , how do I say it, to push and twist, to carefully apply paint behind the grid, gently laying it down, then he heaves and sighs as if the tones to which he had given birth were then torn from him. He always works at a distance from his canvas, always returning to sit at precisely the same little spot that he carefully marked on the floor. He works with the greatest precision, although every time you look at him he’s different, at one moment he is grieved to his soul, then he is singing happily — then livid and wild — every square of tone shows what you get out of him — every little square he paints is another little piece of his sanity lost — it won’t be long before he runs out. I hope that I’m mistaken in this, but … the great genius that leads to madness tosses and turns in his head incessantly. He is surprisingly arduous about his working — kneading, persisting to get it completed. You should see him sometimes when he leaves his studio, frozen solid, stupefied, he walks staring, suddenly yelling — sighing — peering aloft — with damp eyes, as if he was addressing his Virgin (this less out of religiosity than to call on a deity of his art.”⁷

Maybe it is most leading, and also romantic, to find a clue to Mancini’s need for the graticola in the name he chose for the device itself. In his recent book on the artist, author Ulrich Hiesinger gave the word graticola this possible translation: “grating” (as in a confessional window).⁸ For the artist, who was quite devout, though he only painted one religious subject in his career (Saint John the Baptist), his grid may have served as the divider between the mundane and the holy. Through his screen, sins were laid bare, and truths were revealed, and it is possible that the artist felt he could not be a conduit for the talents bestowed upon him from his God without it.

¹ National Museum Wales, Antonio Mancini (1852-1930): Portrait of a Girl, October 5, 2009.

² Ulrich Hiesinger, Antonio Mancini: Nineteenth-Century Italian Master (Yale University Press: New Haven, CT), p. 67.

³ Hiesinger, pp. 88-89.

⁴ Katie Swatland, August 14, 2009.

⁵ Hiesinger, p. 67.

⁶ Hiesinger, p. 105.

⁷ Hiesinger, p. 67.

⁸ Hiesinger, p. 66.